Right here, where in the bright light the past and the present can recognize each other

text by Olga Miłogrodzka

According to Jan Assmann – a German Egyptologist – people live only through the last 80 years of history, which look back over the living generations. Next, the experience gives way to cultural memory, passed from generation to generation.Amongst the residents of Gdańsk a mere 10% experienced the end of World War II, and even less its outbreak. This year’s commemoration of the 70th Anniversary of the Outbreak of World War II aims at retaining a clear picture of 1939 events in the memory of the remaining 90% of the population. It’s a good opportunity to give those events some thought and see what image of war will emerge before our eyes, and what image we want to commemorate.

Cultural memory, in Assmann’s view, has two faces. It can take a potential course, when the knowledge of historic events is subject to passive storing and mindless repetition, or it can take the present course, when the sources of knowledge serve the contemporaries as the points of departure for the brand new interpretations reflecting the context of time and place in which they are made. The relation, described by Assmann, between the semantics of historic time and the present, has been underscored by a wide circle of humanists in the last few decades. Prof. Mieke Bal, for instance, when doing research on Baroque Art and later interpreting the findings, used the term “preposterous history”, indicating chronological precedence of the contemporary events over the past 17th century ones. According to Bal, the present time dictates to us, or even imposes, the way of thinking about the past, somehow shaping it again in its own way. I dare say: September 2009 and September 1939 are both equal heroes of the commemoration. I guess Thyra Hilden and Pio Diaz, whose artistic project will be shown in Gdańsk 1st Sep 2009, would fully agree with the statement. Their project does not attempt to reconstruct historic events, but to see them from the angle of a contemporary world reality, which is better known and better understood. To tell the truth, it seems to be the only thing we can do, we the young generations, if we want to make the images of war from 70 years ago less alien and distant; we should find a point of reference for them, and at least to some extent experience them in our own way.

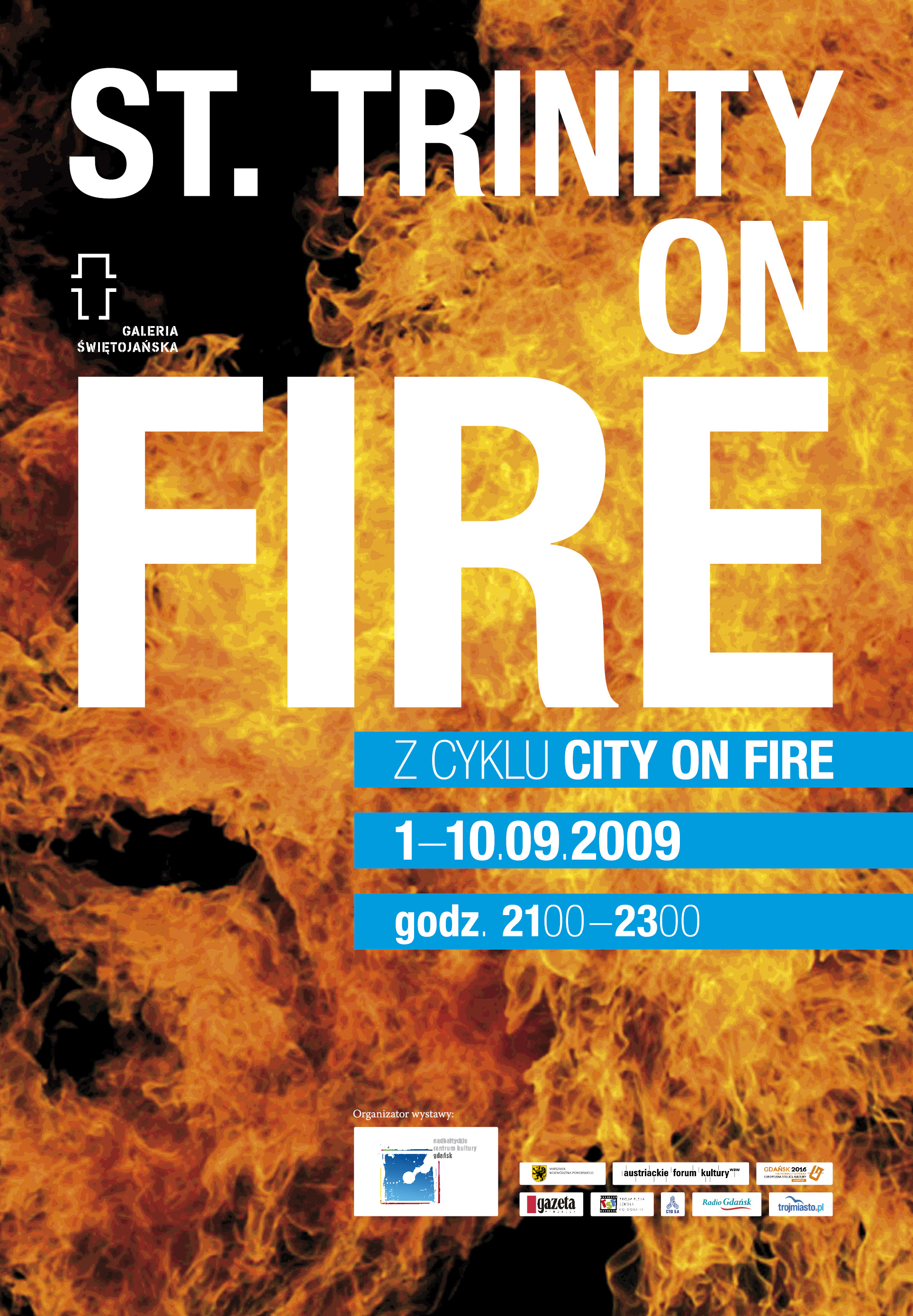

“City on fire” is artistically (but not technically) a very simple work of art. It consists of unreal, but incredibly realistic, clouds of raging and roaring fire. Despite that, when standing in the Holy Trinity Church which is “burning”, it will do to ask a simple question: what can I see? Is it the fire – the distinguishing feature of World War II, the well-known picture from war films, documentaries, photos; the fire from that time, on the one hand terrifying, yet, completely harmless as it’s so distant and fictional? If so, then there could be nothing more misleading and illusive. Because what is the difference between the destructive element of fire which ravaged Gdańsk and Hiroshima in 1945, and the one which razed World Trade Center to the ground a few years ago, or ostentatiously destroyed the Danish flags, or in the recent years claimed thousands of lives in Lebanon, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Iraq, Gaza, Chad, Sudan, Somalia, Sri Lanka, Georgia and many other countries worldwide? I’d say: no difference at all. I even wonder if treating World War II in terms of “the past” should not simply fill us with disgrace.

Therefore, I would compare the picture created by Thyra Hilden and Pio Diaz in Gdańsk Church to the “dialectic picture” by Walter Benjamin; the picture in which the tragedy of both the past and the present meet for a brief moment, so brief and unexpected as the flash of flashbulbs; they recognise and shed light on each other, and bring about a state of emergency. “The past can be seized only as an image which flashes up at the instant when it can be recognized and is never seen again”, Benjamin noted, and added: “Every image of the past that is not recognized by the present as one of its own concerns threatens to disappear irretrievably”. Benjamin attributed the power of redemption to the very state of emergency. At these brief moments, he underscored, the present takes on a Messianic dimension, namely, by the power of bringing the past back to life, and rescuing it from oblivion. Who knows, perhaps it is so. Perhaps experiencing history again, experiencing it through authentic contemporary events is still possible for us. “Every second of time is the strait gate through which Messiah might enter”, Benjamin said. Let’s bear these words in mind too when commemorating World War II.

[translation: Michał Jankowski]

Assmann, Jan. Das kulturelle Gedächtnis. Schrift, Erinnerung und politische Identität in frühen Hochkulturen (Munich: Beck,1992); see also: Assmann, Jan. Collective Memory and Cultural Identity, in: New German Critique 65 (1995). Ibid. Mieke, Bal. Quouting Carravaggio. Contemporary Art, Preposterous History, Chicago: University of Chicago (1999). Benjamin, Walter, Thesis on the Philosophy of History, in: Zdanie 1 (1989).