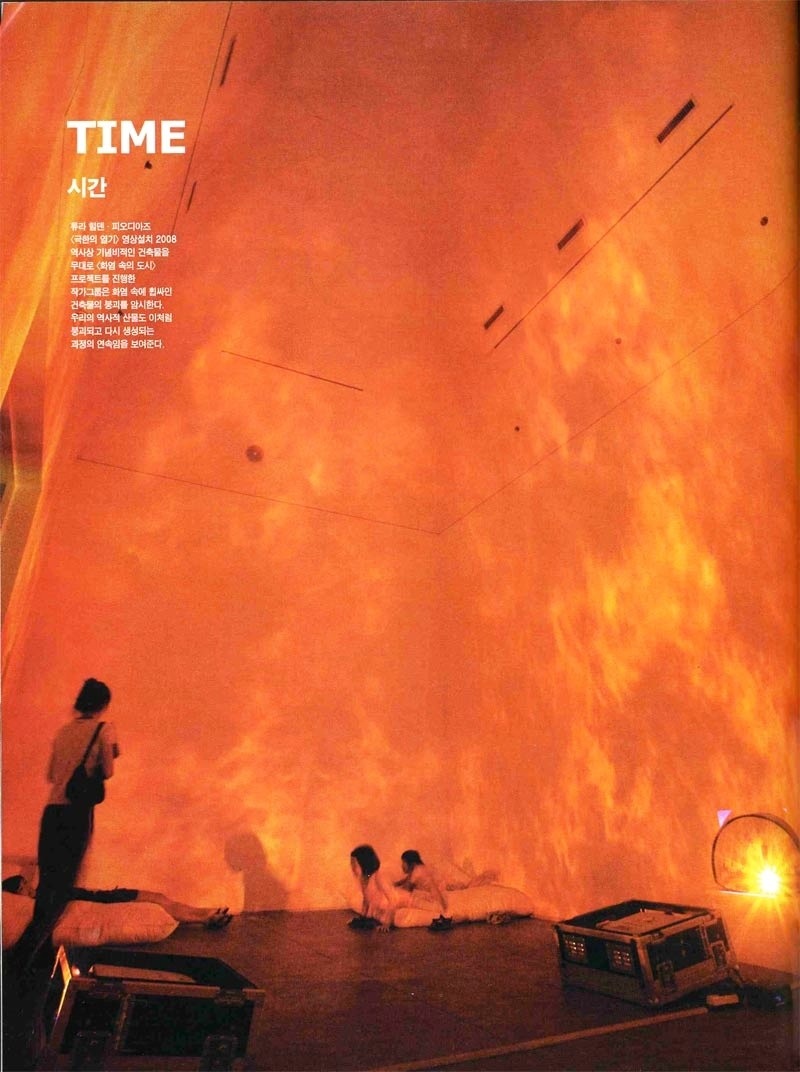

VIDEO PYROMANIACS & pictures of fire related works

By Lisbeth Bonde

Old Houses Ablaze

Thyra Hilden & Pio Diaz destabilize European cultural history by setting monuments on fire.

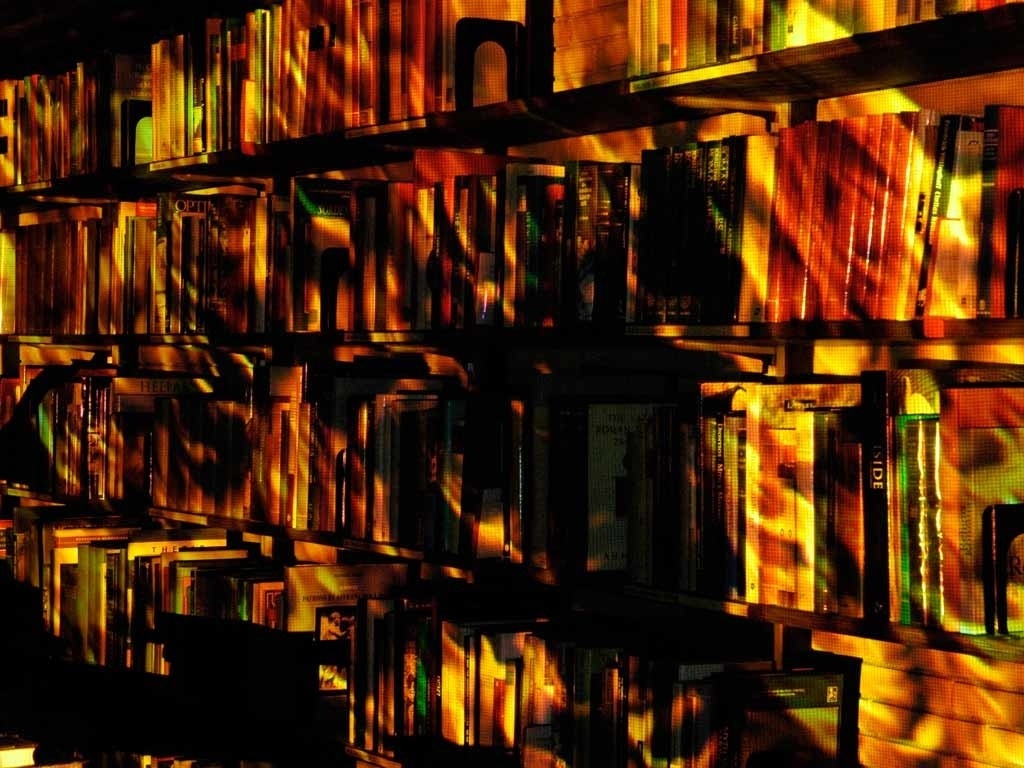

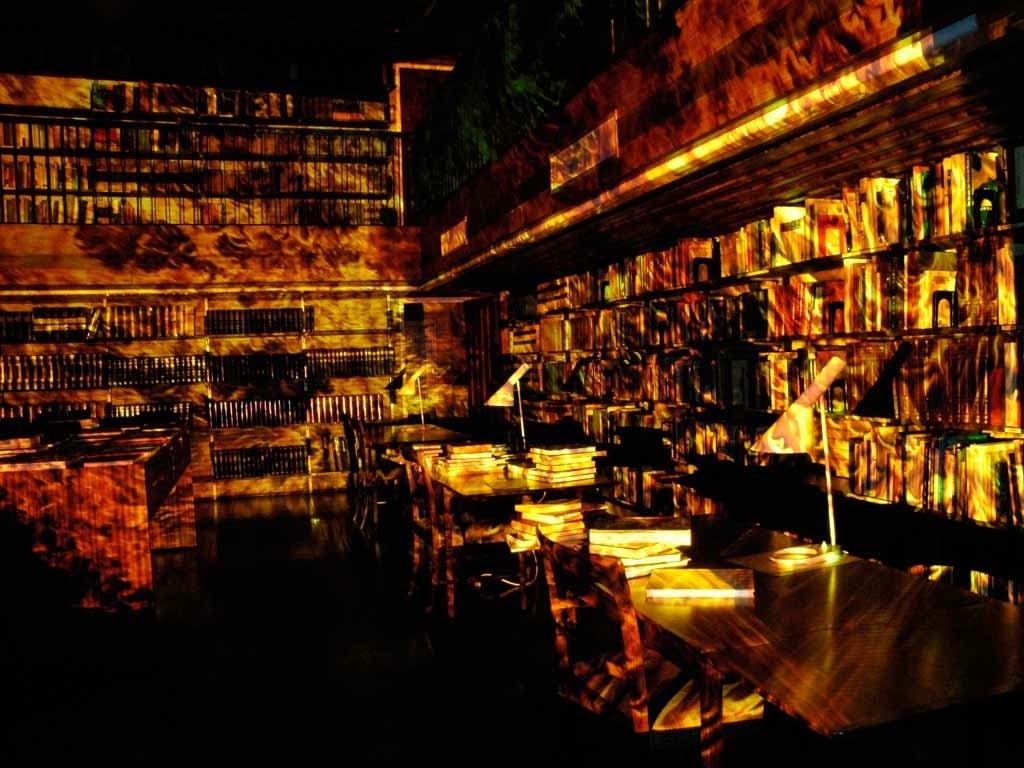

The Danish-Argentinean artist couple Thyra Hilden & Pio Diaz set the monuments of western cultural history on fire in their joint and ongoing video project “City on Fire.” With their seductive and spectacular artistic gesture, they reveal the fragile and transitory nature of these man-made constructions, and thereby destabilize prevailing order. The old monuments serve as weighty expressions for western culture and identity, and have to a certain extent functioned as templates for later constructions in cultural history. As such they constitute a physical foundation for western self-understanding, which the two artists unpack and recast in their edgy work. The artist couple chose these historical monuments and institutions with great care, only to then consign them to the flames in their large-scale and dramatically staged work. These ephemeral works tend to release equal parts of anger and joy from the audience; the illusion is so convincing, and our instinctive reaction to fire so deeply engrained, that we immediately place ourselves on guard when we see such cherished buildings drowning in flame.

Fire is one of the four elements. It is made of incandescent gas and other combustible materials, such as carbon. It is ignited by a spark or through another fire (such as explosions, fire in the oven or in the fireplace), it is summoned forth with a lighter, a match, or a cigarette, – or it can be created when the rays of the sun are caught in a mirror. It arises when a combustible material is supplied with oxygen and exposure to sufficient heat. In nature, forests burn as a part of natural cycles, so that new trunks can spout and new life can emerge. Carbonized wood can be used as a fuel, and the charcoal can be used as a medium to draw or as makeup. All these associations, along with our instinctive fear of fire, are at play both consciously and unconsciously in the story that Hilden & Diaz put forth in their project “City on Fire.” The monuments are instilled with new life – in a sea of fire, they rise again like a phoenix in all their splendor and monumental glory. They appear as flamboyant, illuminated objects of beauty in the fire’s glowing waves. White marble and shimmering, fallen walls turn into gold in the darkness of night. The experience is so realistic, so hyper-real, that only one sensory impression is still needed to complete the experience: heat. The video flames have no all-consuming appetite like real flames, and they won’t make sweat beads on the foreheads of viewer, who might be standing comfortably under rain-soaked umbrellas until the video cannons are silenced and the monumental buildings come forth again with their enormous mass wholly intact in the blackness of night.

Fire holds two contrary properties: it can cause severe damage and destroy essential natural and cultural values when encountered in the form of an all-consuming fire that arises on its own. It is this kind of fire that humans and animals have feared for as long as they have walked the planet. That’s the fire that’s at play here – searing and destructive. But its tamer version, when held in check by fireproof materials such as stone or metal, has been our invaluable friend, ever since Homo Erectus emerged from apes some 700-800,000 years ago and ground two sticks together. Then we’re speaking about cold fire- the word “bonfire” being a direct translation of “good fire…” this is the fire that, when kept under control (such as in a fire pit), people have gathered around for hundreds of thousands of years. Throughout all of our cultural history, controlled fire has acted as a fuel for cultural and technological development. It provides us with light and heat and has been an indispensable tool in our households as part of our cooking, and has also been able to destroy pathogens, aiding our well-being still further. Several millennia ago, fire played the all-important role in our transformation from hunter-gatherer society to an agricultural society when we first burned down the forests in order to sow our fields. Fire has also made it possible for people to move to colder parts of the globe.

But human hands have also exploited controlled fire for destructive purposes, as a weapon of war. In ancient times and the Middle Ages, burning arrows were shot at the towns and homes of enemies, and from ancient Greece we know the story of the Trojan horse filled with Greek soldiers who then shot burning arrows into Troy, which was then reduced to ashes. If we take an enormous step forward to our own time, we observe the Germans burning the earth during their retreat from northern Finland during the Second World War. They set fire to large areas of land, towns, and factories in order to starve and humiliate the victor. From the 20th century onwards we have crowned our enemies with bombs that then explode and set buildings ablaze – with the atomic bomb standing as the most severe form of weaponised fire, which contaminates everything for kilometers around. During the Vietnam War, the Americans used napalm bombs against North Vietnam. These bombs burned everything. And today, USA holds neutron smart bombs that burn everything alive. A bit more primitive is the Molotov cocktail, used in street riots and guerrilla warfare, thrown at the opponent to set smaller areas on fire. It’s a bottle filled with a combustible fluid– such as alcohol or gasoline. The bottleneck serves as a wick, and then the bottle strikes its target; it explodes and sets fire to a targeted, localized area. In Denmark’s 1993 Nørrebro riots, demonstrators overturned containers and cars, setting them on fire in the streets around the black square. Fire conveys chaos and destruction and threatens sudden death.

Fire is also a part of most religious rites in the form of sacrifices, i.e., burning of crops or slaughtered animals for the gods. When the smoke reaches heaven – where most religions imagine that their god or gods reside –the sacrificial smoke becomes theirs. In the Old Testament we know the story of Moses, who saw God in the form of a burning thorn bush, smouldering without flames. God told a frightened Moses that He had chosen him to lead the Israelites out of Egypt to the Promised Land, Israel, which flowed with milk and honey. And Greek mythology tells us of Prometheus as a Titan who stole fire from Olympia and gave it to humankind. Prometheus has thus become a symbol of humankind’s struggle with the gods, and the term “promethean” refers to a lively person, who rebels against a given order. The North American Indians also made use of fire – but in a very special way, as they used it to communicate with subtle smoke signals that could be spotted over long distances on the American plains, and in South America, in the Inca culture; people revered the Sun God, who represented a life-giving fire.

As stated above, fire has its own cultural history. At the same time, it operates metaphorically on many levels. It is said that an old home can catch on fire when the desires of its elderly inhabitants suddenly come ablaze. Desire as a whole often appears metaphorically as fire – we say “you light my fire;” those who demonstrate a “glowing” enthusiasm have a “fire in the soul.” There is no smoke without fire, says an old proverb, suggesting that everything has a cause. “He had a spark,” we say – the spark being fire –when thoughts suddenly spring to mind. In his story “The Temperaments,” H.C. Andersen describes the four elements as equivalent of the four temperaments. The Choleric is as such the “Fire king,” a self-igniting lantern man, who is called forth with a lighter. “Chemistry!” he shouts, knowing what he and the entire world is made of, knowing what parts went together and what parts did not. “I know chemistry! And I know myself, where I come from, where I am going, all of it!” This short-tempered fellow had a violent temperament that burst out into the open, and wherever he went, he laid waste with his tongue of fire. Fire has an innate fury that builds and grows faster when given the right fuel. Fire is not satisfied until everything is turned to ashes and the world is turned back to a barren and carbonized state.

Fire will always be burning one place or another in the world, and so long as it exists, we can reap its benefit. Wherever human activity is to flourish, we tear down in order to build up. Fire is an irrational, ambiguous, and immaterial phenomenon rich in contrasts that can both reap destruction and wrap itself warmly and lovingly around humankind. It can make our cultural roots vanish in the course of a few minutes, and all of our entire modern life incessantly burns away for new technology and new forms of life to be able to constantly grow forth. This fear of fire’s all-consuming power helps intensify the tension experienced in “City on Fire.” Here we see modern technology – namely digital video media –confronted with classic works of architecture – and in this connection there arises a meeting full of contract between orders new and old. These burning scenes by Thyra Hilden and Pio Diaz call the world’s continued existence into question. Through their international-based and monumental approach and enormous statement, the couple’s work is reminiscent of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s massive installation projects.

Lisbeth Bonde is an art columnist for the Danish paper Weekendavisen. She is the author of several books, including ’Kunstnere på tale’ (2001), ’Atelier – kunstnerens værksted’ (2003), SOLO – en monografi om Peter Martensen (2006) and (with Mette Sandbye) ’Manual til dansk samtidskunst’ (2006).